Sunday, August 25, 2019 8:07 am

Ademola Adegbamigbe

President Muhammadu Buhari published an opinion in the Washington Post newspaper in commemoration of August 23rd, the day the UN declared as International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition.

He wrote that four centuries ago, the first 20 documented African slaves arrived on the shores of Virginia. He added: “In the years that followed, millions more were shipped in dehumanizing conditions across the ocean and enslaved. Slavery had, of course, existed before. But this indicated the beginning of a mechanized trade that saw human beings reduced to property on an unprecedented scale.”

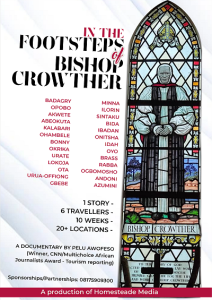

One of the victims of this hideous trade was Bishop Ajayi Crowther, though the vessel that carried him and other captives was lucky to have been rescued by some British anti-slavery frigates on the Atlantic before it sailed to the Americas.

In this 182-year old letter, Crowther narrated how he was captured as a boy, sold, bartered for disposable articles, rescued and others.

It was first published in TheNEWS on 25 June 2016, entitled:

Ajayi Crowther’s 179-year old letter: My capture into slavery and rescue

Ajayi Crowther was ordained as the first African bishop of the Anglican Church. However, his background was rough. He was 12 years old when he was captured, along with his mother and toddler brother and other family members, along with his entire village, by Muslim Fulani slave raiders in 1821 and sold to Portuguese slave traders.

In his 1837 letter to Rev. Williams Jowett, then Secretary of the Church Missionary Society, Crowther narrated his capture into slavery and rescue

By Samuel Ajayi Crowther

Letter of Mr. Samuel Crowther to the Rev. Williams Jowett, in 1837, then Secretary of the Church Missionary Society, detailing the circumstances connected with his being sold as a slave. Fourah Bay, Feb. 22, 1837

Rev. and dear Sir,

As I think it will be interesting to you to know something of the conduct of Providence in my being brought to this Colony, where I have the happiness to enjoy the privilege of the Gospel, I give you a short account of it, hoping I may be excused if I should prove rather tedious in some particulars.

I suppose sometimes about the commencement of the year 1821, I was in my native country, enjoying the comforts of father and mother, and affectionate love of brothers and sisters. From this period I must date the unhappy, but which I am now taught, in other respects, to call blessed day, which I shall never forget in my life.

I call it unhappy day, because it was the day in which I was violently turned out of my father’s house, and separated from relations; and I which I was made to experience what is called to be in slavery – with regard to its being called blessed, it being the day which Providence had marked out for me to set out on my journey from the land of heathenism, superstition, and vice, to a place where His Gospel is preached.

For some years, war had been carried on in my Eyo (Oyo) country, which was always attended with much devastation and bloodshed; the women, such men as had surrendered or were caught, with the children, were taken captives. The enemies who carried on these war were principally the Oyo Mahomendans, with whom my country abounds- with the Foulahs (Fulbe), and such foreign slaves as had escaped from their owners. Joined together, making a formidable force of about 20,000, who annoyed the whole country. They had no other employment but selling slaves to the Spaniards and Portuguese on the coast.

The morning in which my town, Ocho-gu (Osogun), shared the same fate which many others had experienced, was fair and delightful; and most of the inhabitants were engaged in their respective occupations. We were preparing breakfast without any apprehension; when, about 9 o’clock a.m. a rumour was spread in the town that the enemies had approached with intentions of hostility. It was not long after when they had almost surrounded the town, to prevent any escape of the inhabitants; the town being rudely fortified with a wooded fence, about four miles in circumference, containing about 12,000 inhabitants, which would produce 3,000 fighting men. The inhabitants not being duly prepared, some not being at home; those who were, having about six gates to defend, as well as many weak places about the fence to guard against, and, to say in a few words, the men being surprised, and therefore confounded – the enemies entered the town after about three or four hours’ resistance.

Here a most sorrowful scene imaginable was to be witnessed! – women, some with three, four, six children clinging to their arms, with the infant on their backs, and such baggage as they could carry on their heads, running as far as they could through prickly shrubs, which, hooking their blies and other loads, drew them down from the heads of the bearers. While they found impossible to go along with their loads, they endeavoured only to save themselves and their children: even this was impracticable with those who had many children to care for.

While they were endeavouring to disentangle themselves from the ropy shrubs, they were overtaken and caught by the enemies with a noose of rope thrown over the neck of every individual, to be led in the manner of goats tied together, under the drove of one man. In many cases a family was violently divided between three or four enemies , who each led his away, to see one another no more.

Your humble servant was thus caught-with his mother, two sisters (one an infant about ten months old), and a cousin – while endeavouring to escape in the manner above described. My load consisted in nothing else than my bow, and five arrows in the quiver, the bow I had lost in the shrub, while I was extricating myself, before I could think of making any use of it against my enemies. The last view I had of my father was when he came from the fight, to give us the signal to flee: he entered into our house which was burnt some time back for some offence given by my father’s adopted son. Hence I never saw him more-Here I must take thy leave, unhappy, comfortless father! – I learned, some time afterward, that he was killed in another battle.

Our conquerors were Oyo Mahomendans, who led us away through the town. On our way, we met a man badly wounded on the head struggling between life and death. Before we got half-way through the town, some Foulahs (Fulbe), among the enemies themselves, hostilely separated my cousin from our number, here also I must take thy leave, my fellow captive cousin! His mother was living in another village. The town on fire – the houses being built with mud, some about twelve feet from the ground with high roofs, in square forms, of different dimensions and spacious areas; several of these belonged to one man, adjoined to, with passage communicating with each other. The flame was very high.

We were led by my grandfather’s house, already desolate; and in a few minutes after, we left the town to the mercy of the flame, never to enter or see it any more. Farewell, a place of my birth, the playground of my childhood, and the place which I thought would be the repository of my mortal body in its old age.

We were now out of Osogun, going into a town called Isehin (Iseyin), the rendezvours of the enemies, about twenty miles from my town. On the way we saw our grandmother at a distance, with about three or four of my cousins taken with her, for a few minutes: she was missed through the crowd to see her no more. Several other captives were held in the same manner as we we were: grandmothers, mothers, children, and cousins were all led captives. O sorrowful prospect! The aged women were to be greatly pitied, not being able to walk so fast as their children and grandchildren; they were often threatened with being put to death upon the spot, to get rid of them, if they would not go fast as others, and they often as wicked in their practice as in their words. O pitiful sight! Whose heart would not bleed to have seen this? Yes, such is the state of barbarity in the heathen land. Evening came on; and coming to a spring of water we drank a great quantity; which served us for breakfast, with a little parched corn and dried meat previously prepared by our victors for themselves.

During our march to Iseyin, we passed several towns and villages which had been reduced to ashes. It was almost midnight before we reached town, which we passed our doleful first night in bondage. It was not perhaps a mile from the wall of Iseyin when an old woman of about sixty was threatened in the manner above described. What had become of her I could not learn.

On the next morning, our cords being taken off our necks, we were brought to the Chief of our captors – for there were many other Chiefs– as trophies at his feet. In a little while, a separation took place, when my sister and I fell to the share of the Chief, and my mother and the infant top the victors. We dared not vent our grief by loud cries, but by very heavy sobs. My mother, with the infant, was led away, comforted with the promise that she should see us again, when we should leave Iseyin for Dah’dah (Dada),- the town of the Chief.

In a few hours after, it was soon agreed upon that I should be bartered for a horse in Iseyin, that very day. Thus was how I separated from my mother and sister for the first time in my life’ and the latter not to be seen more in this world. Thus, in the space of twenty-four hours, being deprived of liberty and all other comforts I was made the property of three different persons. About the space of two months, when the chief was to leave Iseyin for his own town, the horse which was then only taken on trial, not being approved of, I was restored to the chief, who took me to Dada where I had the happiness to meet my mother and infant sister again with joy, which could be described by nothing else but with tears of love and affection; and on the part of my infant sister, with leaps of joy in every manner possible.

Here, I lived for about three months, going for grass for horses with my fellow captives. I now and then visited my mother and sister in our captor’s house, without any fears or thoughts of being separated any more. My mother told me that she had heard of my sister, but I never saw her any more.

At last, an unhappy evening arrived, when I was sent with a man to get some money at a neighbouring house. I went; but with some fears, for which I could not account; and, to my great astonishment, in a few minutes I was added to the number of many other captives, unfettered, to be led to the market-town early the next morning. My sleep went from me; I spent almost the whole night in thinking of my doleful situation, with tears and sobs, especially as my mother was in the same town, whom I had not visited for a day or two. There was another boy in the same situation with me: his mother was in Dada.

Being sleepless, I heard the first cock-crow. Scarcely the signal was given, when the traders rose, and loaded the men slaves with baggage. With one hand chained to the neck, we left the town. My little companion in affliction cried and begged much to be permitted to see his mother, but was soon silenced by punishment. Seeing this, I dared not speak, although I thought we passed by the very house my mother was in. Thus was I separated from my mother and sister, my then only comforts, to meet more in this world of misery.

After a few days of travel, we came to the market-town, I-jah’I (Ijaye). Here I saw many who had escaped in our town to this place; or those who were in search of their relations, to set at liberty as many as they had means of redeeming. Here were under very close inspection, as there were many persons in search of their relations; and through that, many had escaped from their owners. In a few days I was sold to a Mahomendan woman, with whom I travelled to many towns on our way to Popo country, on the coast much resorted to by the Portuguese, to buy slaves.

When we left Ijaye, after many halts, we came to a town called To-Ko (Itoko). From Ijaye to Itoko all spoke the Ebwah (Egba) dialet, but my mistress spoke Oyo, my own dialect. Here I was a perfect stranger, having left the Oyo country far behind. I lived in Itoko about three months; walked about with my owner’s son with some degree of freedom, it being a place where my feet had never trod: and could I possibly have made my way out through many a ruinous town and village we had passed, I should have soon become a prey to some others, who would have gladly taken the advantage of me. Besides, I could not think of going a mile out of the town alone at night, as there were many enormous devil –houses along the highway; and a woman had been lately publicly executed (fired at), being accused of bewitching her husband, who died of a long tedious sickness. Five or six heads, of such persons as were nailed on the large trees in the market-places, to terrify others.

Now and then my mistress would speak with me and her son, that we should by- and bye go to Popo country, where we should buy tobacco, and other fine things, to sell at our return. Now, thought I, this was the signal of my being sold to the Portuguese; who, they often told me during our journey, were to be seen in that country. Being very thoughtful of this, my appetite forsook me, and in a few weeks I got the dysentery, which greatly preyed on me. I determined with myself that I would not go to Popo country; but would make an end of myself, one way or the other. In several nights, I attempted strangling myself, one with my band’ but had no courage enough to close the noose tight, so as to effect my purpose. May the Lord forgive me this sin! I determined, next, that I would leap out of the canoe into the river, when we should cross it in our way to that country. Thus was I thinking, when my owner, perceived the great alternation which took place in me, sold me to some persons.

Thus the Lord, while I knew Him not, led me not into temptation and delivered me from evil. After my price had been counted before my own eyes, I was delivered up to my new owners, with great grief and dejection of spirit, not knowing where I was now to be led. About the first cock-crowing, which was the usual time to set out with the slaves, to prevent their being much acquainted with the way, for fear an escape should be made, we set out for Jabbo (Ijebu), third dialect from mine.

After having arrived at Ik-ke-ku Ye-re (Ikereku-iwere), another town, we halted. In this place I renewed my attempt of strangling, several times at night; but could not effect my purpose. It was very singular, that no thought of making use of knife ever entered my mind. However, it was not long before I was bartered for tobacco, rum and other articles. I remained here, in fetters, alone, for some time, before my owner could get as many slaves as he wanted. He feigned to treat us more civilly, by allowing us to sip a few drops of White Man’s liquor, rum; which was so estimable an article, that none but Chiefs could pay for a jar or glass vessel of four or five gallons: so much dreaded it was, that no one should take breath before he swallowed every sip, for fear of having the string of throat cut by the spirit of the liquor. This made it so much more valuable.

I had to remain alone, again, in another town in Jabbo, the name of which I do not now remember for about two months. From hence, I was brought, after a few days’ walk to a slave-market, called I-ko-sy (Ikosi), on the coast, on the bank of a large river, which probably was the Lagoon on which we were afterwards captured.

The sight of the river terrified me exceedingly, for I had never seen anything like it in my life. The people on the opposite bank are called E’ko. Before sun set being battered again for tobacco, I became another owner’s. Nothing now terrified me more than the river, and the thought of going into another world. Crying was nothing now, to vent out my sorrow; my whole body became stiff. I was now bade to enter the river, to ford it to the canoe. Being fearful at my entering this extensive water, and being so cautious in every step I took, as if the next would bring me to the bottom, my motion was very awkward indeed. Night coming on canoe, and the men having very little time to spare, soon carried me into the canoe, and placed me among the corn-bags, and supplied me with an Ab-alah (abala) for my dinner.

Almost in the same position I was placed I remained, with my abala in my hand quite confused in my thoughts, waiting only every moment our arrival at the new world” which we did not reach till about 4 o’clock in the morning. Here I got once more into another dialect, the fourth from mine; if I may not call it altogether another language, on account of now, in some words, and then there being a faint shadow of my own. Here I must remark that during the whole night’s voyage in the canoe, not a single thought of leaping into the river had entered my mind, but, on the contrary, the fear of the river occupied my thought.

Having now entered E’ko (Lagos), I was permitted to go any way I pleased; there being no way of escape, on the account of the river. In this place I met my two nephews, belonging to two different masters. One part of the town was occupied by the Portuguese and Spaniards, who had come to buy slaves.

Although I was in Lagos more than three months, I never once saw a White Man; until one evening, when they took a walk, in company of about six, and came to the street of the house in which I was livivng. Even then I had not the boldness to appear distinctly to look at them, being always suspicious that they had come for me: and my suspicion was not a fanciful one, for, in a few days after, I was made the eight in number of the slaves of the Portuguese.

Being a veteran in slavery, if I may be allowed the expression, and having no more hope for ever going to my country again, I patiently took whatever came. It was not without a great fear and trembling though that I received, for the first time the touch of a white man, who examined me whether I was sound or not. Men and boys were at first chained together, with a chain of about six fathoms in length, thrust through an iron fetter on neck of every individuals, and fastened at both ends with padlocks. In this situation the boys suffered the most: the men sometimes, getting angry, would draw the chain so violently, as seldom went without bruises on their poor little necks; especially the time of sleep, when they drew the chain so close to ease themselves of its weight, in order to be able to lie more conveniently, that we were almost suffocated, or bruised to death, in a room with one door, which was fastened as soon as we entered in, with no other passage for communicating the air than the opening under the eavesdrop.

Very often at night, when two or three individuals quarrelled or fought, the whole drove suffered punishment, without any distinction. At last, we boys had the happiness to be separated from the men, when their number was increased and more chain to spare: we were corded together, by ourselves. Thus, we were going in and out, bathing together, and so on. The female sex fared not much better. Thus we were for nearly the space of four months.

About this time, intelligence was given that the English were cruising the coast. This was another subject of sorrow with us – that there must be war also on the sea as well as on land – a thing never heard of before, or imagined practicable. This delayed our embarkation. In the meanwhile, the other slaves which were collected in Popo and were intended to be conveyed into the vessel the nearest way from that place, were brought into Lagos, among us. Among this number was Joseph Bartholomew, my Brother in the service of the Church Missionary Society.

After a week’s delay we embarked, at night in canoe, from Lagos to the beach; and on the following morning were put on board the vessel, which immediately sailed away. The crew being busy embarking us, 187 in number, had no time to give us either breakfast or supper; and we being unaccustomed to the motion of the vessel, endured the whole of this day in sea-sickness, which rendered the greater part of us less fit to take any food whatever.

In the very same evening, we were suprised by two English men-of-war, and on the next morning found ourselves in the hands of new conquerrors, who we at very much dreaded, they being armed with long swords. In the morning, being called up from the hold, we were astonished to find ourselves among two very large men-of-war and several other brigs. The men-of-war were, His Majesty’s ships Mymidon, Captain J.H Leeke, and Iphigenia, Captain Sir Robert Mends, who captured us on the 7th of April 1822, on the river Lagos.

Our owner was bound with his sailors; except the cook, who was preparing our breakfast. Hunger rendered us bold; and not being threatened at first attempts to get some fruits from the stern, we in a short time took the liberty of ranging about the vessel, in search of plunder of every kind. Now we began to entertain a good opinion of our conquerors. Very soon after breakfast, we were divided into several of the vessels around us. This was now cause of new fears, not knowing whether our missery would end. Being now, as it were, one family, we began to take leave of those who were first transshipped, not knowing what would become of them and ourselves.

About this time, six of us, friends in affliction, among whom was my brother Joseph Bartholomew, kept very close together, that we might be carried away at the same time. It was not long before we six were conveyed into the Mymidon, in which we discovered not any trace of those who were transshipped before us. We soon came to a conclusion of what had become of them, when we saw parts of a hog hanging, the skin of which was white – a thing we never saw before; for a hog was always roasted on fire, to clear it of the hair, in my country; and a number of cannon shots were arranged along the deck. But we were soon undeceived, by a close examination of the flesh with cloven foot, which resembled that of a hog; and, by a cautious approach to the shot, that they were iron.

In a few days we were quite at home in the man-of-war; being only six in number, we were selected by the sailors, for their boys; and were soon furnished with clothes. Our Portuguese owner and his son were brought over into the same vessel, bound in fetters; and thinking that I should no more get into his hand, I had the boldness to strike him on the head, while he was shaving by his son – an act, however, very wicked and unkind in its nature. His vessel was towed along by the man-of-war, with the remainder of the slaves therein. But after a few weeks, the slaves being transshipped from her, and being stripped of her rigging, the schooner was left alone on the ocean – “Destroyed at sea by captors being found unseaworthy, in consequence of being a dull sailer”.

One of the brigs, which contained a part of the slaves, was wrecked on a sand-bank: happily, another vessel was near, and all the lives were saved. It was not long before another brig sunk, during a tempest, with all the slaves and sailors, with the exception of about five of the latter, who were found in a boat after four or five days, reduced almost to skeletons, and were so feeble, that they could not stand on their feet. One hundered and two of our number were lost on this occasion.

After nearly two months and a half cruising on the coast, we were landed in Sierra Leone, on the 17th of June 1822. The same day we were sent to Bathurst, formerly Leopold, under the care of Mr (Thomas) Davey. Here we had the pleasure of meeting many of our country people, but none were known before. They assured us of our liberty and freedom; and we very soon believed them. But a few days after our arrival at Bathurst, we had the mortification of being sent to Freetown, to testify against our Portuguese owner. It being hinted to us that we should be delivered up to him again, notwithstanding all the persuation of Mr. Davey that we should return, we entirely refused to go ourselves unless we were carried. I could not but think of my ill-conduct to our owner in the man-of-war But as time was passing away, and our consent could not be got, we were compelled to go by being whipped; and it was not a smalle joy to us to return to Bathurst again, in the evening, to our friends.

From the period I have been under the care of the Church Missionary Society, and in about six months after my arrival at Sierra Leone, I was able to read the New Testament with some degree of freedom; and was made a monitor, for which I was rewarded with seven pence-half penny per month. The Lord was pleased to open my heart to harken to those things which were spoken by His servants, and being convinced that I was a sinner, and desired to obtain pardon through Jesus Christ, I was baptised on the 11th of December 1825, by Rev. J. Raban. I had the short privilege of visiting your happy and favoured land in the year 1826. It was my desire to remain for a good while, to be qualified as a Teacher to my fellow-creatures, but Providence odered it so, that, at my return, I had the wished-for instruction under the tuition of Rev. C.L.F Haensel who landed in Sierra Leone in 1827,through whose instrumentality I have been qualified so far, as to be able to render some help in the service of the Church Missionary Society, to my fellow-creatures. May I ever have a fresh desire to be engaged in the service of Christ, for it is perfect freedom!

Thus much I think necessary to acquaint you to the kindness of Providence concerning me. Thus the day of my captivity was to me a blessed day, when considered in this respect; though certainly it must be unhappy also, in my being deprived on it of my father, mother, sister and all other relations. I must also remark, that I could not as yet find a dozen Osogun people among the inhabitants of Sierra Leone.

I was married to a Christian woman on the 21st of September 1829. She was captured by His Majesty’s ship Bann, Captain Charles Phillips, on the 31st October 1822. Since, the Lord had blessed us with three children – a son, and two daughters.

That the time may come when the Heathen shall be fully given to Christ for His inheritance, and the uttermost part of the earth for His possession, is the earnest prayer of your humble, thankful, and obedient servant.

Samuel Crowther

Source: A Patriot to The Core. Bishop Ajayi Crowther by Professor J. F. Ade-Ajayi